JAKARTA, Indonesia – What girls want for their futures matters. And, according to new survey data, what they want most is the chance to learn.

The study, published 10 August 2023 by the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health, asked more than 700,000 young people aged 10-24 to finish the statement: “To improve my well-being, I want..."

Of the hundreds of thousands of girls and young women surveyed, one in five identified a wish for learning, competence, education, skills and employability.

“In my opinion, the welfare of life starts where we learn and get an appropriate education,” one 18-year-old girl from Jakarta, Indonesia said in her response.

Globally, however, girls are disproportionately denied access to education. One reason is child marriage; around the world, one in five girls are either married or in an informal union before their 18th birthday. Many are subsequently forced to leave school.

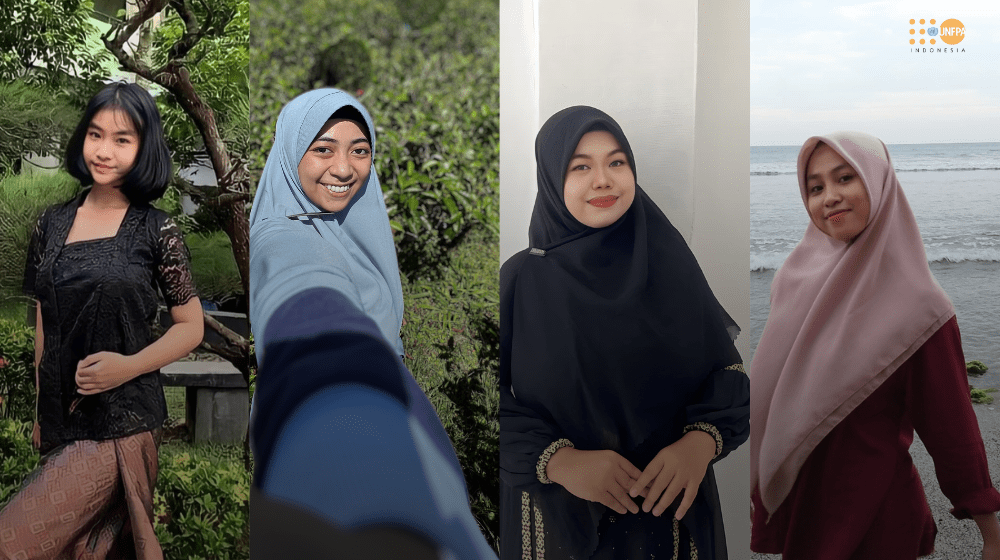

"In my community, most girls want to get [as much] education as possible ... but they face obstacles from their parents' mindset," 18-year-old Carmelia Winnie Joceline from Pontianak, Indonesia, told UNFPA, the UN sexual and reproductive health agency. "I think education is important for women and girls because it’s our right.”

© UNFPA Indonesia/Carmelia Winnie Joceline

Wanting more than marriage

Despite reforms raising the legal age of marriage in Indonesia from 16 to 19 in 2019, the national prevalence rate of child marriage in Indonesia is 11 per cent.

Economic stress, cultural norms and patriarchal values all contribute to how pervasive child marriage remains; research indicates that girls from poor families and rural areas, as well as those with low educational attainment, are at a higher risk of entering unions young.

“It's all because of the mindset that education isn't important,” said 25-year-old student and retail worker Atikah Ratna Sari. “In my [hometown], girls were getting married between the ages of 14 and 17.”

Atikah grew up in Palangkaraya, Central Kalimantan, where two thirds of children live in rural areas and the prevalence rate for child marriage is 19 per cent. The eldest of five siblings, Aatikah has wanted to be a teacher since she was little; yet, some in her family discouraged her from seeking higher education.

“You’ll end up staying at home anyway,” they told her.

© UNFPA Indonesia/Atikah Ratna Sari

Their prediction almost came true when Atikah was 12 years old and relatives from her father’s side of the family took her to live in their village, and then held secret discussions with a man from another village about becoming her husband.

“It was terrifying. Fortunately, my mother found out about it, so I was brought back home in the city,” Atikah said. “My mother had a different perspective; she believed she could support me in obtaining proper education.”

Atikah’s mother’s viewpoint has proven benefits. Research shows a girl’s chances of finishing secondary school decline for each year she is married before her 18th birthday, and potential future earnings are also negatively affected by early unions.

UNFPA works around the world to eliminate child marriage and to keep girls in school. In Indonesia, it has partnered with the Ministry of Women's Empowerment and Child Protection and the Khouw Kalbe Foundation to launch the BESTARI programme, which provides scholarships for Indonesian girls deemed at risk of child marriage or violence.

Atikah is one of 250 scholarship recipients. She had postponed her pursuit of higher education for six years to support the educational dreams of her sister, but after stumbling on an Instagram post for the scholarship, she decided it was also her time to go.

Atikah has since started her first semester of college and is majoring in elementary school education.

“I have always wanted to be a teacher because I want to help children get an education,” she said. “I dream of establishing a free school where there are no age restrictions and no uniforms. They don’t need to pay or buy books because I will provide for them for free.”

Like clear water

Six hundred million adolescent girls live on the planet today. Among their multitude, tens of thousands of future doctors, teachers, lawyers, mothers, activists and artists lay in wait, ready to bloom under the right conditions.

“Every girl is born with boundless potential – to learn and thrive, to lead, inspire and change the world,” Dr. Kanem said in her International Day of the Girl Child statement. “They represent a generation of innovation and action, leading calls for justice and a world that works for all.”

BESTARI shows how a supportive environment can empower girls to grow into their potential. It also reveals how empowering women to fufilll their rights has the knock-on effect of widening access to rights and choices in their communities and societies at large.

20-year-old Ade Nurchalisa wants to put her education towards eliminating gender-based violence. © UNFPA Indonesia / Ade Nurchalisa

A young woman takes a photo of herself in an outdoor setting.

"BESTARI made me realize my dream is to create a technological innovation that empowers women – a platform where women can report gender-based violence, voice their concerns, get help and possibly even connect with law enforcement,” said 20-year-old Ade Nurchalisa, who is majoring in informatics engineering. “It's essential for women to express themselves and assert their rights, just like men. Education gives women a voice equal to men's.”

© UNFPA Indonesia / Ade Nurchalisa

Another member of BESTARI’s first cohort dreams of becoming a university lecturer.

“I want to be a university lecturer to contribute to the nation's intellectual development,” said Mulyana, 21, who is studying information technology. “I want to be like clear water, useful for others.”

21-year-old BESTARI scholarship programme participant Mulyana plans to get married when she’s mature and has built her career.

© UNFPA Indonesia/Mulyana

Having seen girls around her unable to continue their education because of child marriage, 21-year-old BESTARI scholarship programme participant Mulyana plans to get married when she’s mature and has built her career.

*This article was originally published on the UNFPA website to commemorate the International Day of the Girl Child.