Yunie can’t fight the tears that are rolling down her eyes while she is recounting losing her parents in the tsunami disaster that hit her hometown, Banda Aceh, on 26 December 2004 morning. It has been 20 years since that sorrowful tragedy, but the memory and pain are still fresh in her mind. “Everything was swept away by the ocean… including my mother. She was gone.”

Two decades ago, the devastating Indian Ocean tsunami that struck Aceh claimed over 167,000 lives (out of 230,000 in 14 countries) and left half a million people displaced in the Aceh province and Nias island in Indonesia. The catastrophic event shattered the region's social fabric and caused immense physical destruction. Women and girls were the most affected. Yet, amidst the immense loss and suffering, stories of resilience and hope emerged. After 20 years, we reflect on what lessons we have learned from one of the largest humanitarian crises that Indonesia has ever seen in our modern history.

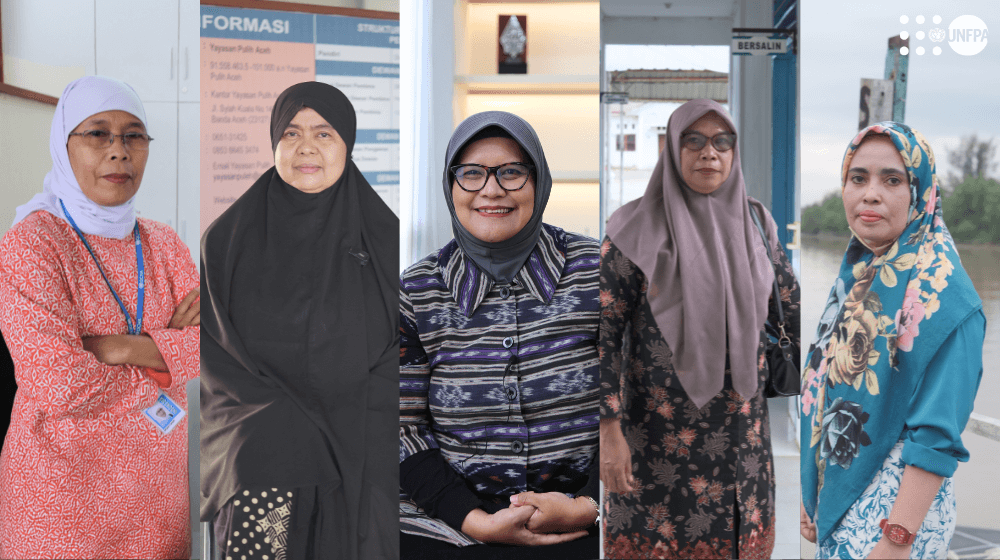

(Photos: UNFPA Indonesia/Itsnain G. Bagus)

The Tsunami Impact on Women and Girls

The tsunami did not only inflict loss and trauma but also led to a gender imbalance in the surviving population in Aceh—as more women than men perished—and a decline in living standards due to the loss of land, housing, documents, and livelihood opportunities. That’s the key finding from the 2005 assessment by UNFPA, in collaboration with Oxfam Great Britain and the Women Studies Centre of Ar-Ranirry State Institute for Islamic Studies in Aceh entitled “Gender and changes in tsunami-affected villages in Nanggroe Aceh Darussalam province”.

“Women had to save themselves while wearing long clothes, which is mandatory in Aceh’s regulation… This is my analysis. And then, most women cannot swim. And, before saving themselves, they would rescue their children and loved ones first,” said Rosilawati Anggraini (Rossy), the Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH) Coordinator of UNFPA Sub Regional Office for the Caribbean, who started working as a Reproductive Health Advisor at UNFPA Indonesia in 2005.

(Photo: UNFPA Indonesia/Itsnain G. Bagus)

Childcare and domestic responsibilities still and usually largely fall on women, who then face additional burdens while supporting others and addressing the emotional needs of traumatized children and men.

The Story of Yunie

Like most Acehnese, the tsunami has turned Yunie’s life upside down. Not only did she lose her parents; she also lost her home and her life as she knew it. After being stranded in the sea for 5 days, she had to stay in displacement for 7 years.

(Photo: UNFPA Indonesia/Itsnain G. Bagus)

“We lived in tents, and each family had their own tent with a capacity of 7 people. I was with my brother and sister, but my sister had to move to another shelter because she didn’t feel comfortable sharing the tent with other people,” the 41-year-old woman explained.

We would gather in the evenings to share stories… Hearing stories of others, I realized that there were people who suffered more than me,” Yunie recalled.

She also found a job to help her survive while helping her fellow internally displaced people. “We received different kinds of assistance, but the most impactful one was meeting Dian Marina, the Aceh coordinator of Pulih Foundation. She offered me a job as a case worker and facilitator for women victims of domestic violence and conflict,” Yunie said. “The pay was not much, under Rp 1,000,000, but it was enough as I was young and we had food at the camp.”

Eight years after the disaster, she finally returned home to the plot of land her parents left behind, with a new home rebuilt by humanitarian aid. “But the neighborhood was dark and empty. There was no electricity at that time. So, I would not go outside because I was scared. There were just the two of us at home, my brother and I,” Yunie described. “It was only in the tenth year after the tsunami that we finally got electricity.”

The Story of Dian

Dian Marina from Pulih Foundation Aceh lost her little sister right in the middle of the tsunami, when they were seeking safety on the second floor of their neighbor’s house, after their one-story house exploded. “I don’t know where she went. She just disappeared. I don’t know where or how she fell, as she didn’t make a sound at all,” the 52-year-old woman recalled. “For the first two weeks, I kept on crying, remembering my sister. Especially since it was raining when it happened. So whenever it’s raining, I would think of her and wonder where she is. Because we were very close. I was devastated. But as time went by, I started to accept it. I thought, maybe it’s for the best.”

(Photo: UNFPA Indonesia/Itsnain G. Bagus)

One of the things that helped Dian survive the traumatic impact of the disaster was meeting people from the Pulih Foundation, a psychosocial nonprofit organization that participated in the tsunami disaster response. “They asked me to join them and provided their staff with capacity building. That’s where I learned about psychosocial support, gender, gender-based violence, and others. I got involved in the psychosocial support for tsunami survivors at displacement camps,” Dian said.

Although Dian admitted to having never received any psychological treatment for her trauma, she thought working at Pulih Foundation helped her. “Because they knew I was a survivor, they would often talk to me and ask me how I felt. I felt that they cared about me,” Dian said.

I felt resilient because I felt strong enough to share my story a few days after the tragedy. So many organizations interviewed me.”

The Story of Nurasiah

“After the earthquake, the water on the beach near our house receded, and there were a lot of fish fluttering. So my mother-in-law and my son went to the beach, with the other villagers, to catch the fish,” Nurasiah, a 52-year-old midwife in Calang, Aceh Jaya, recalled. “My mother-in-law said the sea dried up;, and there’s so many fish… The potential of a tsunami didn’t cross our minds at all. We didn’t think the receding beach meant a tsunami was coming.”

Fortunately, Nurasiah and her family—her 5-year-old son, 8-month-old daughter, and mother-in-law—were all safe. They climbed the hill before their house for safety and stayed there for 3 months. Her husband, who was in Meulaboh, also made it safely to Calang 10 days after the tsunami, even though one of his legs was severely injured. Because of trauma, Nurasiah refused to live in the displacement camps and chose to stay on the hillside in a makeshift camp until they moved to a temporary home built by the Indonesian Red Cross.

Nurasiah and her family had to survive on the hill with very little food and water, which they shared with their neighbors. Once, they endured diarrhea from eating rice submerged in mud due to a lack of food.

Inset: Ahlan, the baby born during the disaster, pictured at age 10 with his mother, Eva, on the right. Nurasiah and Eva have remained close friends, a bond forged through resilience and shared survival.

(Photo: UNFPA Indonesia/Itsnain G. Bagus)

Despite that, she managed to help a woman deliver her baby on the grass with no medical tools at all at night. “We didn’t have anything to cut the baby’s umbilical cord or to wrap the baby. I had to use a thread from a bandana someone was wearing until a soldier came with a knife,” Dian told the story. Fortunately, the childbirth went well, and the mother and the baby were taken to Medan, North Sumatra, afterward for the needed care. Until today, Dian and the mother remain good friends and neighbors.

After that, Nurasiah, who has been a midwife since 1994, served at a temporary clinic, helping women and survivors throughout the tsunami response. “Midwives play a critical role in emergencies. Midwives can do so many things," Nurasiah said.

My role and priority as a midwife was not only to care for pregnant women and provide advice and psychological support to women and children, but I was also there to help victims with any type of medical attention needed.”

The Tsunami's Impact on Communities

The tsunami left a lasting impact on Aceh's communities. According to Dian, Aceh has generally changed so much after the disaster.

“The tsunami impacted Aceh in all aspects. The social structure changed because a lot of families were totally wiped away. And some families lost some of their members. And the sadder fact is that some were subject to trafficking,” Dian explained. “Many Acehnese children were brought outside, either adopted by new parents or brought away by relatives. Many lost their homes.”

“And then the most common impact was trauma. Many people suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder, PTSD. Some couldn’t get on a boat or were too scared to see the sea,” she elaborated. “But for mental health disorders in general, there was research that found that the psychological impact was not very severe. Yes, there were severe psychological disorders, but it didn’t even account for 1 percent of the affected population,” Dian said. “Maybe because Acehnese people are religious. Acehnese people have the faith that there is a life after death. That the deceased are not gone. We will meet them again one day. That’s what makes us strong,” she added. “And also we have a community. Traditionally, we are accustomed to helping and caring for each other.”

Dian thinks the tsunami also had some positive impacts. “In terms of infrastructure, Banda Aceh has become more beautiful... After the tsunami, the roads became nicer, the markets became nicer, and the schools became nicer,” she said. “And it’s now a lot safer. Before the tsunami, nighttime was tense. It was scary. None of us dared go outside at night unless we wanted to risk losing our lives,” Dian said, referring to the protracted conflict that besieged Aceh before the tsunami.

Humanitarian Response that Prioritized Women and Girls

The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) in Indonesia responded swiftly to the urgent needs of the affected communities, especially women and girls, inc collaboration with local, national, and global partners. Contraceptive needs at that time were high. Many survivors had to give birth without basic necessities. And women and girls living in shelters faced an increased risk of gender-based violence (GBV). Recognizing that women's needs don't cease during crises, UNFPA distributed dignity kits, restored reproductive health services, provided psychosocial support, and prevented GBV.

These efforts helped prevent pregnancy-related complications, offered counseling for trauma recovery, and empowered women through skill training and income-generating activities in the four most affected districts–Banda Aceh, Aceh Barat, Aceh Jaya and Aceh Besar. UNFPA also supported a special population census to determine the population impact of the Tsunami in Aceh and Nias–a small neighboring island also affected by the disaster–in 2005.

(Photo: UNFPA Indonesia)

“My job at that time as the reproductive health advisor was ensuring that women’s needs, including pregnant women and mothers giving birth, are prioritized… with the immeasurable damage on health facilities, reproductive health needs were often overlooked or unmet,” Rossy said.

When we asked the women what they needed, they asked for contraceptives and menstrual pads. Before the tsunami they were using pills or injectables, and they were worried about getting pregnant in displacement,” she elaborated.

Rossy shared an interesting story about how reproductive health needs were treated as an afterthought. “Metro TV, the only television station that could get in, broadcasted the Aceh people’s need for menstrual pads. After that, truckloads of menstrual pads came, but they forgot about the underwear! Because they didn’t pay attention to the fact that you cannot wear menstrual pads without underpants,” Rosy recalled.

This situation led to UNFPA’s first distribution of clean delivery and hygiene kits, now known as “dignity kits”, which have become a trademark component of UNFPA’s humanitarian response worldwide. Pioneered in the wake of the Indian Ocean tsunami, dignity kits comprise essential items like hygiene products, sanitary napkins, a flashlight, and a change of clothes that women and girls need to protect themselves and maintain hygiene and respect in the face of disasters. In short, dignity kits are essential to self-esteem and confidence–and critical to protecting women and girls in emergencies.

Lessons Learned

The Aceh tsunami underscored the critical need to integrate reproductive health services and psychosocial support into disaster response efforts. UNFPA's experience in Aceh highlights the importance of data-driven strategies, community engagement, and women's empowerment in building resilient communities.

Women's participation was minimal during the Aceh tsunami crisis; they were often excluded from aid distribution and community decision-making. “There was so much aid, like a flood of aid. So many things were built. But the assistance was not very participative, not involving the community. The community was viewed as mere victims, not as survivors, people who are empowered and need to be involved," Dian lamented.

Another valuable lesson learned is in coordination and collaboration. “Because it’s such a large-scale disaster, the international attention was enormous. We came up with the term ‘tsunami of funds’ because of the incredibly large funds coming in,” Rossy said. “Since we never had any experience responding to such a massive disaster, the Government wasn’t prepared. We didn’t have a strong coordination mechanism, so there were a lot of duplications and overlapping in programming. So, it was tough coordinating the international aid.”

Titi Moektijasih, Humanitarian Affairs Analyst of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA), highlighted an important lesson on disaster preparedness. “I think everyone in Aceh at that time felt the same way as me… We had no idea that there would be a tsunami or even what a tsunami was,” Titi recalled.

(Photo: UNFPA Indonesia/Itsnain G. Bagus)

The most important lesson from the tsunami in Aceh was preparedness… It triggered the passing of law number 24/2007 on disaster management. The civil society wouldn’t have pushed for the bill without the tsunami,” Titi said.

“Then, in 2008, the National Disaster Management Agency (BNPB) was established, and there’s a dedicated agency responsible for disaster management at the same level as a ministry. And then there is the BPBD at provincial and district levels,” Rossy added.

Rossy also added that the Tsunami served as a major turning point for humanitarian aid nationally and globally. “There’s a shift in paradigm after the tsunami in Aceh. Before, we only focused on disaster response. But after, we became aware that we must be prepared for all aspects of disaster, from preparedness, response, to rehabilitation and reconstruction,” she elaborated. “So it was a wake-up call for Indonesia, the international community, and the UN… We needed the wake-up call to realize that what we had done was not enough,” Rosy affirmed.

20 Years On: Moving Forward

Twenty years later, the lessons learned from the Aceh tsunami have shaped global disaster preparedness and response strategies. But have we turned them into real changes that could improve our disaster resilience?

(Photo: UNFPA Indonesia/Itsnain G. Bagus)

New systems have been implemented both at national and global levels. “The UN launched a humanitarian reform after facing similar issues in response to a large-scale Pakistan earthquake in 2005. We didn’t want disaster response to be business usual, so there must be change,” Rossy explained. “There are three critical elements of humanitarian reform: the first is the presence of a humanitarian coordinator in every country. Second, a cluster system consisting of groups of organizations and agencies focusing on different issues, which improves coordination and collaboration and prevents overlapping. The third one was an integrated financial system called the Central Emergency Response Fund that pools the UN funds for organizations to apply through the cluster system. That way, the use of funds would be more effective. Additionally, there’s the flash appeal, an integrated funding mechanism that pools funds from all donor countries,” Rosy continued.

Progress has been made in Indonesia, but we still have a lot of homework. “The Disaster Safe Education Unit (Satuan Pendidikan Aman Bencana - SPAB) has been integrated into the school curriculum. But how many schools have implemented the SPAB? For example, have we considered the risks when building a house? Do we need two exit doors in each house? Do we have the disaster preparedness bag ready at home?” Titi said.

Disaster preparedness is not only the Government’s job, but it’s key. I hope that 20 years after the tsunami we are all more aware that we live in a disaster-prone country. I hope the 20th anniversary of the tsunami in Aceh will trigger us to understand that the first safety responsibility is on us. And most importantly, I hope that the Government continues to develop the preparedness more systematically and structured,” Titi affirmed.

-----

Rahmi Dian Agustino

UNFPA Indonesia Communications Analyst

Magda Sarsevanidze

UNFPA Indonesia Communications Intern